I’m a big fan of concise stories. If a writer fills a three-volume science fiction epic with 2000 pages of detailed worldbuilding, intriguing speculative concepts, and captivating character arcs, that’s all well and good, but if that writer can get that down to 300 pages, that’s better. And if a writer goes further and nails it in 150 pages—well then, that writer can only be Jack Vance.

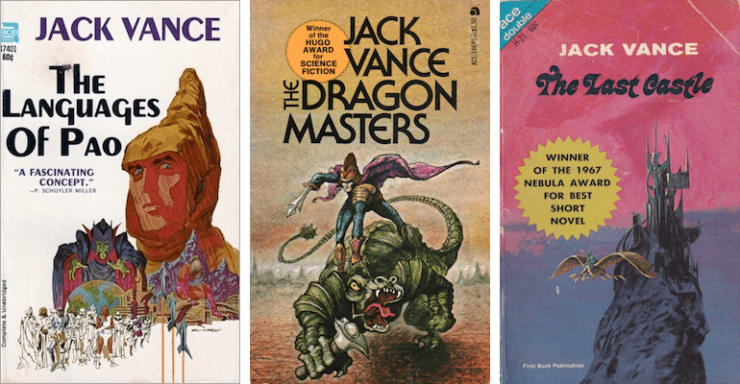

Vance produced well over 70 novels, novellas, and short story collections over the course of his writing career, creating fantasy stories and mysteries as well as science fiction, and even producing a substantial number of doorstoppers that would have impressed George R. R. Martin with their girth. Vance’s extensive oeuvre has its imperfections—especially glaring today is his near-complete lack of interesting female characters—but at their best the books set an excellent standard for the construction of strange new worlds. Three tales in particular, The Languages of Pao (1958), the Hugo Award-winning The Dragon Masters (1962), and The Last Castle (1966), squeeze artfully assembled civilizations into focused, tight paragraphs. Other authors might have used these worlds as settings for bloated trilogies, but Vance quickly builds each society, establishes his characters, delivers the action, and then is off to create something new. I can’t think of any other author who put together so many varied worlds with such efficiency.

The Languages of Pao

Vance opens The Languages of Pao (the longest of these three novels, at 153 pages) with a two-page chapter bringing readers up to speed on the planet of Pao, concluding with a paragraph about the local language. On Pao, the inhabitants don’t use verbs or comparisons, because “[t]he Paonese sentence did not so much describe an act as it presented a picture of a situation.” This static, passive language and the mind-set that evolves from it becomes an obstacle for Beran Panesper, in line to rule the entire planet until things go awry. The young man’s decades-long journey from heir to refugee to conspirator against Pao’s new rulers is the spine of the story, one which plays with the idea that thought can’t outrun language, and thus language makes us who we are.

Beran escapes from Pao to hide from the usurper Bustamonte, but is back within roughly a decade, in league with a ‘wizard’ named Palafox. Palafox’s plan to return Beran to power involves changing the nature of Paonese society by making a collection of new languages for new classes of citizens to speak. This plan requires a lot of time to implement—at least a generation—and in the meantime Beran travels his world, immersing himself in several regions and laying the seeds of a culture that will transform his planet.

While there’s a lot more to say about Beran’s fraught alliance with Palafox, and his realization that he’s changing Pao perhaps for the worse with his complicated scheme to rid the planet of its current tyrants, the most striking thing about the book is its depiction of Pao. For the story to work, readers need to know not just what this place looks like but what its social structures are, how its people think and feel, and how it can change, and Vance covers all of that without ever pausing in Beran’s journey.

The Dragon Masters

One of Vance’s best-known novellas opens with a description of the main character’s dwelling. Joaz Banbeck is a dragon-lord of the planet Aerlith, a place where feudal noblemen keep pens of dangerous creatures collectively known as dragons, used in their warlording activities. There’s more to this place; Aerlith has several fiefdoms, each ruled by a family, and each family has a history, with various prominent ancestors. And we haven’t even gotten to the dragons and where they came from yet (there are several variations and distinct functions). Plus the dragons aren’t even the most remarkable or mysterious thing about Aerlith.

By page 14, chapter 2, we get to the story of Joaz Banbeck’s ancestor fighting an invading alien army known as the Basics, then we get more stories of rivalries among the dragon-lord families. By chapter 3, the social complexity has approached Dune levels. Yet there’s another element of the story that Vance has hinted at—the doings of an enigmatic collective of naked men known as the Sacerdotes. In fact, the story first opens with a sacerdote mysteriously entering and then vanishing from Banbeck’s apartment. Had Vance stretched all of this out, the pieces of this story—the family legacies, the Sacerdotes, the various classifications of dragons—would seem like digressions, but he keeps everything moving at a rapid pace. The book’s only 137 pages long, and there’s no room for fat. The main event of The Dragon Masters, the return of the Basics and their army of modified human slaves, gets started around page 95. The resolution is as swift and memorable as the rest of the story.

The Last Castle

Given how prolific Vance was, it’s not surprising that he reused various story elements in his books. A number of his science fiction stories begin with a galactic troubleshooter of some kind walking down the gangplank of a starship onto the multicolored turf of an alien planet, and there are other echoes and callbacks found throughout his works. The Last Castle seems to borrow some pieces from The Dragon Masters, but it’s very much its own story, and reading one right after the other didn’t feel like a retread at all. Again, Vance presents a society built on a feudal foundation, wherein humans live in fortified cities, and again an army of aliens wreaks havoc on these citadels. A major difference, however, is that unlike the people of Aerlith, the inhabitants of New Earth’s castles may have inadvertently caused the attacks, and they certainly don’t know what to do about them. These major differences require Vance to describe the very specific culture and customs of Earth’s castle-dwellers, which he of course does with expert concision, serving up an elaborate civilization with enviable economy.

Buy the Book

All Systems Red: The Murderbot Diaries

The Last Castle begins with an amazing opening line: “Toward the end of a stormy summer afternoon, with the sun finally breaking out under ragged black rain clouds, Castle Janeil was overwhelmed and its population destroyed.” We go from there to Castle Hagedorn, whose clan leaders and elders meet to figure out how they can withstand the bellicose Meks, once their servants and now the force that’s sweeping across the planet, killing all of the humans who, centuries earlier, returned to their homeworld to set up luxurious palaces for their lives of ease. These humans have gathered alien races and repurposed them as a support staff, with Peasants as general laborers, Birds as transport, Phanes as decorative playthings, and Meks as the ones who keep everything running. By page 19 we’ve met Xanten, a clan chief who sets out to keep the Mek army from seizing the spaceship hangars that the humans haven’t used in ages. The real question of the story, though, isn’t what has caused the Meks to riot. It’s whether or not the humans deserve to survive.

The ‘gentlefolk’ of Castle Hagedorn are so caught up in their time-honored rituals and ceremonies—Vance describes a couple of them, though we’re told there are plenty more—that they can barely focus on the murderous army marching toward them. And the various aliens that play involved parts in this society all get descriptions and backgrounds, but throughout the story rather than all at once (it took me a few chapters before I realized that Birds were not, in fact, birds). As with The Dragon Masters, the story ends with a great conflict, only the sides are not the same as in the earlier tale and the stakes are distinct as well. While Joaz Banbeck was the product of a battle-scarred civilization, cut off from his terrestrial history and adrift in a universe laden with mystery, Xanten comes from a society of leisure and formality, groaning under the weight of its history.

As a coda to this survey of a portion of Vance’s output, around the time he wrote these three science fiction tales, Vance also wrote a short story in which he packed one of his most intricate cultures into a mere 35 pages. “The Moon Moth” (1961) is an extraordinary example of worldbuilding, set within a one-of-a-kind mystery. Edwer Thissell comes as a consulate agent to the planet Sirene, where natives wear masks at all times. Not only that, but speech is musical, with the rhythms, tempos, and melodies varying depending on the statuses of the addresser and addressee. AND speech must be accompanied by one of several small instruments worn on the belt. Failure to follow these Sirenean norms can result in death. All of this (including the names and functions of the various belt-instruments) is not just described with precision, but within the course of the story, which has Thissell receiving a message that he has to detain a criminal newly arrived on Sirene—who of course is wearing a mask, as is everyone else. It’s a feat that many other authors would have stretched into a novel, or filled with paragraphs of clunky exposition, but Vance, as always, breezes past bloat and tedium, depicting a fully-formed world with the fewest possible brush strokes.

Hector DeJean relives the pop-culture highlights of his misspent youth every day in his head. He’s written about television, superheroes, and TV superheroes for the Criminal Element.

I love Vance, but his use of multi-paragraph encyclopedic footnotes is not what I would call “tight” worldbuilding.

“The Moon Moth” is possibly my favorite short story by Vance (well, aside from the Dying Earth stuff, which sits atop my particular Vancean pedestal), and perfectly encapsulates everything I love about his writing.

Any overview of Vance at all intended for the unfamiliar really ought to make considerable mention The Dying Earth stories.

Walker White: That’s true, and I remember Vance using a lot of those footnotes in the Demon Princes books. I picked these three books/novellas out because they exemplify what a proficient job of world-building he did when he kept things concise, though he didn’t always.

Cacogen: I wanted to keep this roundup science-fiction, and I’ve only just finished the first Dying Earth book. I think another piece looking at Vance’s fantasy world-building would also be worthwhile, though a little more difficult–the world of the first Dying Earth book isn’t quite as consistent as the ones here (heroes are often journeying into places that defy their understanding of culture and history), and Lyonesse seems to have one of those slightly overstuffed worlds that contrast with those here (but George R. R. Martin liked it). Those aren’t criticisms of either books–it just strikes me that world-building the fantasy books is less of the point.

I find that Vancean “worldbuilding” is a product of the Vancean worldview and his favoured style: the complex, cruel and arbitrary societies he imagines are the perfect foil for his individualistic protagonists.

I loved Vance’s footnotes. The dry parody of academic language was consistently fun, IIRC Vance always claimed that one of his major influences was P. G. Wodehouse. Although he, mostly, there are exceptions, doesn’t imitate Wodehouse, his love for language and dry sense of humor was one of the most attractive aspects of his work.

“his near-complete lack of interesting female characters”

Jean Parlier, Mieltrude Hever, Alice Wroke, The Flower of Cath, Skirlet Hutsenreiter, Suldrun, Glyneth, Madouc, Wayness Tamm…I could go on. I haven’t even mentioned the mysteries.

The length of Vance’s works is very much a function of the conventions of the time, starting with the pulps (which cost us perhaps 20,000 words of Big Planet) and moving on to Ace and Daw paperbacks. That he found these limits constraining is evidenced by the length of his later works, the trilogies Lyonesse and Cadwal, the stand-alone Night Lamp, and his swan song Ports of Call/Lurulu, a single novel that had to be published in two parts.

Which doesn’t mean I disagree with the premise. No doubt, Vance managed to live within the limitations of the times and crafted gems at many different lengths.

And incidentally: The Languages of Pao was originally published in two differently abridged versions. The Vance Integral Edition published the only complete edition of this story, which was also used by Subterranean Press in its limited edition, and by Spatterlight Press for its ebook and its paperback. To the best of my knowledge, all other versions are one abridgement or the other. If anybody knows of an exception, please correct.

The Spatterlight Press website seems to be no longer functional, and their last entries on Facebook and Twitter date from 2015. Anyone know what happened?

The e-book edition of the Spatterlight Press Languages of Pao is listed at Kobo books. I presume this would also be true for Kindles.

I’ll have to give it another try; it’s one of the few Vance books that didn’t impress me, in part because I simply didn’t buy the premise.

@10 John

Thanks. The cover (on the UK Kobo site) says Gateways Essentials. Wikipedia says GE started using the Spatterlight editions in 2013, while Amazon lists their edition of Languages of Pao as published in 2011. Do you have better info?

I read The Moon Moth almost forty years ago and yet when you mentioned it I remembered it and its vivid details and, as you say, intricate world building. What an amazing writer he was.

@11 MadLogician The site was down for maintenance but is available again.

@13 — That is a huge relief. Now I just have to try to remember my login info for the site …

@10: I always assumed that the premise of TLOP was a classic SF ‘what if’: what if the strong version of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis were true?

Speaking of language, Vance was one of the great prose stylists of American SF – that distinctive, mannered language is one of the ways he so successfully and quickly built worlds that were simultaneously extremely strange and yet relatable

I recommend his autobiography; This Is Me, Jack Vance!

How many SF writers, in their boyhood, traveled in a covered wagon? That was just the start of a fascinating life.

Vance is perhaps my favorite author of all time, as could be surmised from my ‘nym. I think his tightest worldbuilding is in the ‘Demon Princes’ tetraology- he described multiple worlds in each novel, each of which could have been the basis of a multi-novel series. He only dedicated a chapter or two to worlds such as Sarkovy, but who wouldn’t want to read more about the planet of poisoners?

I’m throwing my hat in the ring with all of the people singing the praises of The Moon Moth. I recently got my brother-in-law, a genre aficianado, to read it and he loved it. My favorite line from the story has got to be: “If the Home Planets want their representative to wear a Sea-Dragon Conqueror mask, they’d better send out a Sea-Dragon Conqueror type of man.”

I also recommend The Miracle Workers, a novella which first appeared in Astounding, so it was tightly edited to pare down a lot of Vance’s glorious prose. The protagonist, Sam Salazar, is my all-time favorite Vancean hero, specifically because he is initially portrayed as a mooncalf. Also, the magazine cover art illustrating the story is, forgive me, astounding, with the circuit diagrams on the jinxman’s robe being a particularly nice touch.

My favorite passage from The Moon Moth has to be

Also, and I’m frankly surprised I waited this long to post it:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oiOt6eW0pZI

(Hmmm … Doesn’t seem to be displaying a thumbnail or anything, but it’s Vance, at age 96, jamming on ukulele and kazoo.)

“How many SF writers, in their boyhood, traveled in a covered wagon? “

Jack Williamson comes to mind.

“Williamson was born April 29, 1908 in Bisbee, ArizonaTerritory, and spent his early childhood in western Texas. In search of better pastures, his family migrated to rural New Mexico in a horse-drawn covered wagon in 1915.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jack_Williamson

@@@@@ 20, MichaelWalsh

Jack Williamson comes to mind.

That’s two.

I came across ‘The Blue World’ only recently. It’s a good example of what is being discussed, and by extension, vintage Vance.

A minor correction: The hero of The Languages of Pao is named Beran Panasper — for he is, indeed, the bearer of all his people’s hopes.

This is science fiction, not fantasy. Beran’s ally and antagonist, Lord Palafox, is not a wizard but a high-ranking “Breakness Dominie”, who can fly and shoot rays from his hands not by magic but with implanted technology. The misogynistic and egomaniacal super-scientists of Breakness trade their technology for the use of surrogate mothers to bear their sons (never daughters).

Here we see how Vance can enrich a fantasy trope by construing it as science fiction. Similarly, in The Dragon Masters, the dragons are not dragons at all, but intelligent aliens bred by humans into various forms useful for their internecine wars. (Meanwhile, the aliens are doing exactly the same thing with human captives.) This is why the humans call the unaltered aliens, “Basics“.

Incidentally, when I reread Pao a few years ago, my biggest difficulty was slowing down enough to enjoy the language and the story. By today’s standards, a 1500-page trilogy containing the same story would be considered on the short side — and we have adjusted our reading speed to match!

@7/Steve Sherman: The lengths of Jack Vance’s works are only partly a function of the time they were published. The pressure to expand his Hugo-winning novellas, “The Dragon Masters” and “The Last Castle” (which also won the newly established Nebula Award) into full-length novels must have been considerable, but he never did. He wrote something else instead.

Speaking of awards, “The Moon Moth“ is the Vance story selected by the Science Fiction Writers of America for their Hall of Fame, covering the years prior to the establishment of the Nebula Award.

In 2012, the artist Humayoun Ibrahim published a nifty graphic novel version of “The Moon Moth” that should not be missed.

There are also a lot of audio recordings of Vance books out there. I picked up a bunch when Audiobookstand.com went out of business. When read out loud, Vance’s habit of concision is quite helpful, where “modern“ (read “over-written”) books can take forever to get to the point.

taras: Misspelling Beran Panasper’s last name (or title) is indeed my fault. The story does, however, refer to Palafox as a ‘wizard,’ which is why I used that word, though like the ‘dragons’ in The Dragon Masters, the word means something different from what we would assume. And I second your opinion of Humayoun Ibrahim’s version of “The Moon Moth”–it’s absolutely wonderful.

Jack Vance has long been my favorite author. His world-building has always lent color and depth to the story. But his real strength is in character building and the story plots themselves. Where else do you find as much attention given to the nemesis as to the hero? Where else do you find a nemesis whom you can root for almost as much as the hero?

@taras: I concede that I never heard Jack speak about it, nor is it mentioned in any interview I’ve ever seen, but the constraints of the pulps in particular were very real, even ignoring the extreme case of Big Planet. Note for example that the two last Demon Prince novels, written more than a decade after the first three and unlike them never appearing in a magazine, are more than 10,000 words longer. In general, the novels that appeared first in the pulps are shorter, the only exception I can think of being Trullion: Alastor 2262.

Nor am I aware of any suggestion that any of the novelets be expanded. The only instance of that in Vance’s entire career is the expansion of The Kragen to become The Blue World (incidentally a great favorite of mine, woefully underappreciated).

Or perhaps it’s not the only instance: consider the case of Night Lamp. There exists what Vance called an outline, entitled Nightlamp. which at nearly 60 Kwords is longer than some of the earlier published novels. Rather than one more round of revision, which would have been needed to finalize it for publication, Vance expanded it to 145 Kwords, a length well beyond anything from the Ace and Daw period. (Shameless plug: the shorter version is available from Spatterlight Press in the Backstage with Jack Vance series, and is well worth reading in its own right.)

I’m not really sure what we’re arguing about. One of Vance’s many excellences is his ability to give the reader the sense that each work has neither a word too many nor too few (despite the assertion of some critics that his endings are hastily written: I would say rather that they lack the padding we are accustomed to from so many other authors).

To Kirth Girthsome @17 above, that “Astounding” cover art for “The Miracle Workers” is great. Thank you. I had never seen it before; any idea who the artist is?

Along with Jane Austen, Jack Vance is my favorite author, and both for the same reason: their skill at creating a sense of place. I re-read both all the time. Thanks for this article!

@JohnnyMac The cover is by Kelly Freas.

@beth In a review at Amazon, I described it as Jane Austen meets Jack Vance. Since we share favorite authors, there is a good chance you too will like Suzanna Clarke’s Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell, if you don’t know it already. There is also a very good TV adaptation, but of course one should read the book first.

My favorite Vance opening is from his rather obscure novel The Houses of Iszm:

I hope I’ve got it right – that’s from memory, not transcribed, but it raises so many questions. How can a house be female? Why do people want to steal them? What makes houses so valuable?

After an opening like that, failing to read on is (to me at least) unthinkable.

My favorite Jack Vance is the sequence in the middle of The Palace of Love, in which the chosen guests travel from their landing field to the Palace. I joke that this is what won him his Nobel Prize in Literature.

@27/Steve Sherman: One indication there was a demand for a longer version of the two award winners, “The Dragon Masters” and “The Last Castle”, is that, even though they were too short, they were nonetheless eventually published as individual mass-market paperbacks: very skinny ones with very large print.

Over the years, reading Hugo Award nominees, it often struck me that the best works were in the novella category. (This was before the award was corrupted by politics, so I’m not sure it’s still true.) Too long to be easily placed in magazines or anthologies, and normally too short to publish as books, the novellas were written with blithe disregard of commercial necessity, neither truncated nor padded.

When Night Lamp came out in 1996, the first thing that struck me was that here was Vance, at the age of 80, suddenly back at the top of his game. The second thing was that the book seemed to me a novel and its sequel, published as one volume only because the industry believed book buyers wanted longer books.

Similarly, the five book “Demon Princes“ series was reprinted as two volumes, while the four book “Tschai Planet of Adventure” series came out as a single volume.

@33/taras

Exactly. The publishing world had changed, the market no longer demanded 60,000 word mass market paperbacks, but 120,000+ word trade paperbacks.

Go back to the Ace doubles, and the length constraints are even greater. Gold and Iron and Big Planet, at full length only 45 and 52 Kwords, were nonetheless brutally abridged (the former of course as Slaves of the Klau) from their original magazine appearances (the former as Planet of the Damned). Neither was improved by the surgery.

Vance was in every sense of the word a professional writer. When asked what was the most satisfying aspect of his work, he invariably replied, “Getting the check.” If there had been a demand for an expansion of The Dragon Masters or The Miracle Workers or The Last Castle, his most highly regarded novellas, you can bet he’d have pocketed the advance and done the job, just as he did expanding The Kragen to The Blue World.

Nor did Vance ever have any difficulties getting novellas accepted at lengths around 20-30 Kwords. Besides these, there were Chateau d’If, Telek, Crusade to Maxus, Son of the Tree, Abercrombie Station, The Houses of Iszm, Rumfuddle…

Interesting that you describe Night Lamp as Vance “back at the top of his game.” It was preceded by Lyonesse and The Cadwal Chronicles. Were those hackwork?

@34/stevesherman161: Obviously there are infinite gradations between “masterpiece” and “hackwork”! It’s no disgrace when an author loses a step or three in his 80s and 90s. And it’s no accident that nearly every work by Vance recommended above dates from the 1950s or the 1960s.

Similarly, there are infinite gradations between following your muse and being a hack who will write whatever the market demands. Nor should one treat a wisecrack as a solemn pronouncement of an author’s philosophy of writing.

Heinlein, for example, used to crack wise about competing for “Joe’s beer money“, and that the high point of a writer’s day is just before the mail arrives; while the low point of the writer’s day is just after the mail arrives. Yet, instead of cranking out whatever the public wanted, he constantly experimented and pushed the outside of the envelope. He certainly wanted to make money, but that wasn’t all he wanted.

What I do recall Vance saying — I think it was in the introduction to one of the Underwood-Miller collectors’ editions of his work — was that, as he wrote his science fiction, he had in mind what the precocious 16-year-old reader he once was had loved.

@35/taras: Yeah, I remember that remark; can’t find it offhand. Maybe in an interview? To Jack Rawlins, he described his audience as “highly intelligent young men”.

In the early 40s, Vance produced the stories we now know as The Dying Earth. He couldn’t find a publisher until 1950; it might have disappeared forever but for Hillman, whose edition almost immediately sank into obscurity. This rejection led him to tone down his style, to adapt to the pulps of his day. After 10 years or so he had become established in the field, and had more freedom to be true to himself. He often described Clarges (To Live Forever, 1956) as “the first story of the kind I write today”.

Let me be clear: I’m not arguing that Vance’s considerations were exclusively commercial, only that he had to adapt to the realities of the market in order to make a living. Indeed, I consider it an aspect of his greatness that despite those constraints he produced work of the quality of “The New Prime”, “Abercrombie Station”, “Noise” or the original versions of Planet of the Damned and Big Planet.

Nor do I have any doubt that he took great pride in his work, to the point of being hypercritical of his early stories. Looking for the quote about his audience brought me to this exchange in the Rawlins interview (Demon Prince: The Dissonant Worlds of Jack Vance, 1986, IMO the best critical study of Vance’s work), relevant to the Heinlein remark you cite:

RAWLINS: Heinlein once said that when he writes a book he imagines someone standing in the store with two dollars in hand trying to choose between a six-pack and the book, and he concluded, “I try to be better than the beer.” I get the impression you think more highly of your work than that. Is that true?

VANCE: Yes, I think it’s true.

Finally, I don’t at all agree that his final works show the loss of a step. For my money, Lyonesse is his masterpiece, Cadwal, Night Lamp and Ports of Call are among his finest works (I understand but don’t share the view that Throy is a weak conclusion of that trilogy)–and that’s without even taking into account the blindness that resulted in Lurulu requiring seven years to complete. Tastes vary, of course.

I confess, the “Lyonnesse” trilogy made so little impression on me, on its first publication, that I promptly forgot what the books were about. Which turned out to be a blessing, when I picked up the audiobook editions last year. Reading the books “for the first time“, as it were, I found the trilogy pleasing, with its unbiddable princesses and its engineer prince (who escapes an oubliette by building a tower out of the remains of the previous inmates); though I would never classify it with Vance’s best.

On the other hand, the third volume, Madouc, won the World Fantasy Award, so you’re certainly not alone in admiring it.

Now you’ve tickled my curiosity. How does Vance’s unique approach to dialogue work when somebody else is reading it to you?

Just found this site and I was very pleased to do so as Jack Vance is my favourite SF author. For me “The Moon Moth” is his most memorable short story and is the one I would give to a friend who didn’t know Vance to read. “The Dragon Masters” I first read as a teenager and I still have the original magazine in which it was published (Galaxy, I think, without looking) and the paperback version. The main problem I have with Jack Vance is that I re-read everything I have got of his every 10 years (thereabouts) and then I have trouble adjusting to the language and style of other authors for a while. I have a theory that Vance didn’t write all of his novels. I think that many of them were actually non-fiction travel books that accidentally slipped through a wormhole in time from the future and fell into Jack’s hands. He then wrapped a story around them and passed them off as his fiction. I’m particularly thinking of Night Lamp and Ports of Call, to name just a couple. I’m sorry that he wasn’t better financially rewarded for his work and that he’s not around to continue writing.

Tim Underwood once speculated that Norma was the actual author, because every time he visited the Vances, Jack was working on the house while Norma was busy at the typewriter.

I sympathize with the frustration of not having any Vance left unread. That’s why I was so delighted by the two Backstage volumes we recently published at Spatterlight Press. While the stories aren’t new–these are outlines or early versions of finished works–there is some unfamiliar material, as well as the insight into Vance’s process of creation.

And of course unless you have read Big Planet, Gold and Iron (AKA Slaves of the Klau) and The Languages of Pao in their Spatterlight (i.e. VIE) unabridged versions, there is in fact some unread Vance still awaiting your attention.

@40 — Years ago Vance was GoH at a con — I think it was Magicon Worldcon 1992 — and at one session the fans were basically climbing over Norma to get to Jack. I could tell she was a bit miffed. So I sat down and talked to her for a while.

The Vance Integral Edition is a sore point. I didn’t realize there would be no copies for sale after the subscribers were satisfied! I expect I’ll pick up a set cheap as they die off …

I use the phrase, “elegant mausoleum”, to refer to things like the VIE and the “Virginia Edition” of Heinlein’s works.

@39 — Vance would write as he traveled. His heroes are always stopping in to colorful, eccentric inns with ingeniously rapacious landlords. I’ve always suspected these were based on real establishments.

@41 — If it helps, the VIE editions are mostly or entirely available electronically, either directly from the Jack Vance website or from Amazon. (When I was picking them up several years ago, there were a few titles that they couldn’t offer directly for sale in the US due to licensing reasons, but in all of those cases I was able to buy the mass-market eBook edition, send proof of purchase to the website, and they just added the VIE edition to my account.)

I do also have a full CVIE set, but it’s so unwieldy that I can’t imagine actually reading from it, especially with the eBook versions available.